What Did Southerners Have to Say about the Vietnam War?

Book Note: Joseph A. Fry, ed., Letters from the Southern Home Front: The American South Responds to the Vietnam War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2023).

Book Note: Joseph A. Fry, ed., Letters from the Southern Home Front: The American South Responds to the Vietnam War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2023).

Andy Fry tells us in his newest book that Southerners had a lot to say about the Vietnam War. Much of what they wrote to national leaders and newspapers was in support of winning the war. But they also wrote a lot that was poignant, prescient, and heart-breaking, especially about the experience of losing loved ones in the war.

Letters from the Southern Home Front is a great follow-up to Fry’s earlier (and longer) book, The American South and the Vietnam War: Belligerence, Protest, and Agony in Dixie (University Press of Kentucky in 2015). In many ways, this book lets the reader see the raw material that historians use to draw their conclusions. Fry reprints at length 303 of the more than 1,200 letters that he found printed in newspapers and tucked away in constituent mail folders; he used many of these to draw conclusions in his earlier book. But now he’s offering you the opportunity to read along and see what Southerners at the time thought and wrote about the war in their own words. And some of the chapters include as many as 72 different letters to show the range of opinion across the years of the conflict.

From the beginning, Fry shows that Southerners’ regional views shaped how they looked at the conflict in Vietnam. For example, in 1964 (shortly after U.S. Marines landed in DaNang, South Vietnam) a North Carolinian rhetorically asked their Senator “what we would think of a foreign country [landing] troops on our shore to settle the negro question.” (p. 2) In another example, Fry cites a Georgian writing to his Senator in 1972 (as the war was almost over): “As Southerners we should know that the greatness of a people is not merely their ability to win, but their ability to accept defeat when defeat is inevitable.” (p. 2) As Fry lets Southerners speak for themselves, he moves us beyond the polling data that shows the general trends in opinion throughout the Vietnam War. He has divided the book into six chapters, each with a short contextual introduction (to help us recall what was happening when these letters were written), and then he reprints the letters (with initials instead of names and omitting irrelevant information).

Chapter 1 presents the letters from pro-war Southerners, who made up the majority. As Fry points out, those in the South often wanted complete victory and therefore opposed President Lyndon B. Johnson’s limited war in Vietnam. For example, in November 1964, the mother of an Air Force serviceman in Humboldt, Tennessee, wrote Johnson, “This matter of service and war is nothing new to me, but at least back in 1943 we knew who we were at war with and for what we were fighting. Today we do not even admit to being at war. This is my plea! Either take a firm stand on foreign policy even at risk of all out war, or pull out of Viet Nam completely.” (p. 41)

The next chapter shifts to anti-war Southerners, who pollsters found were more likely to be women, people of color, and people with less education. (p. 7) In terms of regional distinctiveness, Fry notes that even those writing with an anti-war perspective focused on their patriotism, denied being radical, and asserted that their criticism did not extend to U.S. soldiers. (p. 76) An Oak Ridger writing to Senator Albert Gore in 1966 stated, “Frankly, I’d rather negotiate in humility than be guilty of committing genocide against those people who have never done a thing to us.” (p. 82)

Black Southerners are the focus of chapter three—but these are primarily letters to the editor of African-American newspapers, since Fry couldn’t identify race in the archived letters. (p. 4) Fry noted overall that Black Americans were primarily interested in how the war would impact the on-going Civil Rights Movement. For example, a February 1968 letter to the Louisville Defender stated, “We would not have the unrest in our cities if it were not for the knowledge that the war in Vietnam is draining away our resources so that there is no money for improving conditions in the ghettos.” (p. 140)

“Southern Families”—the title and topic of chapter four—represent those who sent their family members to fight in Vietnam as well as those who lost those loved ones. Fry points out that Southern states had 22% of the nation’s population but provided 30% of its soldiers, sailors, and airmen—and suffered 27% of its fatalities. (p. 163) A woman from Knoxville, who had lost a nephew in the war, pleaded with Senator Gore in 1966: “We ask you, in the name of one young Tennessee Corporal’s family, and all of the other families we do not know, Americans and Asians, to make every effort in your power, as a Senator, as a national Democratic leader, to help bring this war to some sort of settlement, not a Pyrrhic victory.” (p. 171).

Chapter five is a bit different, as it tackles two distinct topics. Tennesseans didn’t write much on Arkansas Senator J. William Fulbright—whose televised Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings challenged both Johnson’s and President Richard Nixon’s conduct of the Vietnam War. But citizens of the Volunteer State had lots to say about the treatment of Lieutenant William Calley, a Floridian and the only soldier prosecuted for the 1968 My Lai massacre. Tennessee Senator Bill Brock received letters from 3,500 constituents on the issue (p. 225). A letter from a Knoxville woman expressed one of the consistent themes in this correspondence: “We send our soldiers to fight a war in a country where life is held cheaply; a country where women and children fight as savagely as the men; a country where it is almost impossible to tell your friends from your enemies; and where a man must kill for his own survival.” (p. 233)

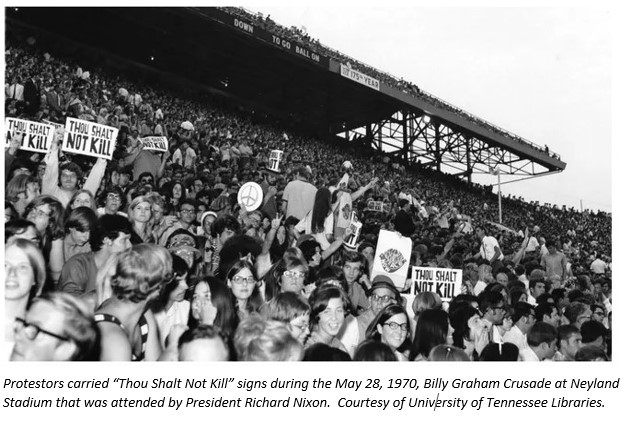

In the last chapter, Fry provides Southern letter-writers’ hostile and impatient views of antiwar protestors, who they tend to identify as students. But students in the South were less likely to be engaged in anti-war protests than their peers in other regions. Nonetheless, some 3,000 students at the University of Tennessee participated in protests in May 1970—the high point of student activism against the war. Tennesseans, such as a Spring City letter-writer, exclaimed bitterly “that our men are facing death on the frontiers of democracy while others of their age are being rabble-roused by hardcore communist sympathizers or actual undercover cell workers.” (p. 275)

Letters from the Southern Home Front breathes life into the complex views Americans expressed about the Vietnam War. It is a great resource for teachers and anyone interested in better understanding the war from a Southern perspective.

→

→

The East Tennessee Veterans Memorial: A Pictorial History of the Names on the Wall, Their Lives, Their Service, and Their Sacrifice by John Romeiser with Jack H. McCall. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2020. Hardcover, $45.00)